June of 1862 saw a marked change in policy how Union authorities in Kentucky dealt with Confederate sympathizers. On May 27, 1862, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton appointed Brigadier General Jeremiah T. Boyle as the new military commander of Kentucky. Boyle assumed his position on June 1, 1862. His predecessors had followed more conciliatory measures whereas Boyle believed “There are many so-called Union men in Kentucky who still cling to a hope of reconciliation and believe in a policy of leniency. I believe in subjugation--complete subjugation by hard and vigorous dealing with traitors and treason. Any other policy I beg to say in my opinion will be ruinous to us in Kentucky.”

|

Brigadier General Jeremiah T. Boyle

Source: Wikipedia |

After James A. Garfield's departure in early spring of 1862, Colonel Jonathan Cranor had taken command of the Union troops in Eastern Kentucky. After the Battle of Middle Creek, Garfield had implemented a policy of kindness. Before he left the Big Sandy Valley, Garfield instructed Cranor to see to the protection of citizens' rights and persons. He stressed that, "While all force and rebellion against the Government must promptly be put down, it must also be remembered that the people in this valley are to live together as fellow-citizens and neighbors after the war is over. All that we can do to inaugurate peace and concord among them while the army is here should be done." However, Cranor believed in sterner methods and found in Boyle a commander who was much more aligned with his own personal views. Thus began a series of arrests that would continue throughout the summer of 1862.

Although the majority of detainees were men, Boyle also began targeting suspected rebel women who showed their loyalty to the Confederate cause either as vocal supporters, spies, smugglers, guerrillas, or even as soldiers. While military authorities discounted women's activities at first as insignificant they soon began to realize the potential damage these women could cause. Up to this point, women had taken full advantage of the code of chivalry that called for women to be protected and cherished which generally shielded them from closer scrutiny and arrest. Incarcerating women was considered barbarous and publicly condemned by many. However, a defiant Boyle declared, "The women think they will rule Kentucky but I will show them they can't do it while I am military governor."

Cynthia Stewart was the wife of Johnson County attorney James E. Stewart who was a political prisoner at Camp Chase since his arrest shortly after the Battle of Middle Creek. She was living in Catlettsburg when Union authorities began monitoring her letters she was writing to her husband for any contraband news. It angered her that her private correspondence would be exposed so publicly and read by so many, to the point that she felt like giving up writing letters altogether. On July 2, 1862, Cynthia noted in one of her letters that, "there was a lady arrested here & sent to prison this week I did not know her sent to Louisville."

The lady in question was Nancy Jane Duncan who first appeared in Eastern Kentucky on June 5, 1862, when she traveled up the Ohio River on board the Steamer Izetta and landed at Catlettsburg. According to the porter of the boat, "she had Seven heavy trunks on board, three of which were unloaded or put off here with her, and the other four were by her direction put off at Ceredo."

|

| Gallipolis Journal, June 5, 1862 |

According to local informants, Mrs. Duncan passed through Catlettsburg, "pretending that she was trying to get to Carter county. Her movements excited suspicion at the time. She had several trunks very heavily laden with what is pretty well understood to be arms for the guerrillas in Morgan county." Provost Marshal Captain Matchett, 40th OVI, noted, "None of this baggage was inspected that I know of ~ It is very probably that the trunks contained Revolvers and Gun Caps and Cartridges."

It wasn't an unreasonable assumption, considering that other women had smuggled similar contraband across enemy lines. Women found creative ways to accomplish their objective, including concealing articles in coffins. It is unknown who the intended recipients of Nancy Jane Duncan's trunks were. As a note of interest, just a few miles above Ceredo, at Holderby's Landing, lived Sarah J. Stewart, wife of James Stewart, who had two sons in the Confederate army. At some point, Mrs. Stewart and her friend Mrs. Miller had gone through the lines into Kentucky, at Catlettsburg, in order to secure medicine to be sent by sympathizers into "Dixie." Both women were arrested as spies and held for some time, pending investigation. It was only through the efforts of a family friend, Dr. J. D. Kincaid, that the women were released.

Nancy Jane Duncan did not linger at Catlettsburg. According to Provost Marshal Matchett she was closely watched after she left town with the remaining three trunks, "and her conduct was such as to satisfy people of her mission." The most likely mode of travel would have been one of the steamboats that plied up and down the Big Sandy River. The first stop on her journey was Cassville, in Wayne County, Virginia (now West Virginia), a small town situated right across the river from Louisa, Kentucky, a Union strong hold. At Cassville, she met and was welcomed by the families of James Stone, David Mitchell and Washington Ratliff. She boarded with James Stone whose wife Nancy maintained a hotel in town. Stone was a merchant and had come under suspicion of being a Southern sympathizer very early on in the War. Nancy Jane Duncan may have been a relative. (Stone was the s/o Ezekiel Stone & Edith Elizabeth Duncan)

His close neighbors were David Mitchell, who operated a saddler shop, and Washington Ratliff who owned a small farm. While at Cassville, Nancy Jane Duncan seemed to have struck up friendships with James Stone's daughter Miss Edea Stone, as well as Miss Marey Mitchell, David Mitchells daughter and Miss Nancy Ann Ratliff, Washington Ratliff's daughter. It is unclear how much time Nancy Jane Duncan spent in Cassville. Still carrying one or more of her heavy trunks, it is very likely that she enlisted the help of a trusted companion to convey them to Morgan County either by wagon or pack mule. Considering the circumstances, it was a dangerous mission to travel alone, especially as a woman. When she left town, she crossed the Big Sandy River by ferry and into Louisa.

Nancy Jane Duncan did not remain in town any longer than necessary in order to avoid drawing too much attention to her person and was soon on her way to Morgan County. The most logical way for her to travel would have been on the road to Blaine, which is present-day KY Rt. 32. However, her presence did not escape the attention of Union authorities who may have been alerted about her in advance. She later noted, "they followed Me from Louisa to take My bagig but as they Dideant overtake Me the first Day they turned back." Her journey would have taken her past the house of Claibourne Swetnam, another well-known Confederate sympathizer, where she may have spent the night. Over the years Swetnam welcomed many travelers in his home, which would also include CSA General Humphrey Marshall just nine months later.

|

Claibourne Swetnam House, Blaine, Kentucky

Source: Marlitta H. Perkins Collection |

From Blaine, Nancy Jane Dunan's route continued on the main road to West Liberty, passing by Sagraves Mill to the junction with the Paintsville road. A few miles further another road forked off, leading through a mountain gap (near present-day Isonville) and up Newcombe Creek. A small bridle path leading from Kendall Branch connected Newcombe with the Middle Fork of Little Sandy River. It was somewhere in this area where Wood Lawn post office was located and where Nancy Jane Duncan's contact person William Green resided. Wood Lawn's post-master was Lewis Kendall whose brother Jesse, the former post-master, was now serving in the Confederate Army.

|

| Morgan County Postmasters, 1850s and 1860s |

William Green was, in all likelihood, William Wellington Green, Sr. His wife was Sarah "Sallie" Hutchinson. William's grandmother was Jael Ellen Duncan before she married Samuel Stallard II. Again, it is possible that Nancy Jane Duncan was related to her host. She addressed him as "brother" but it may not have been meant literally but more figuratively, as in "brother in arms."

If Nancy Jane Duncan was, indeed, carrying military supplies in her trunks as was suspected, it stands to reason that they may have been intended for Fields' Company of Partisan Rangers. At the time of her visit to the Middle Fork/Newcombe Creek area, the unit was in the early stages of formation in Morgan and Carter Counties. The commander was William Jason Fields (b. 1819, s/o James Anderson Fields & Elizabeth Maness) who was serving his fourth term as Carter County sheriff when the Civil War began. He subsequently joined the 5th KY Infantry (CS) and served as 2nd Lieutenant of Company G. After resigning his commission in 1862, he returned to Eastern Kentucky and began recruiting Fields' Rangers. His 1st cousin Preston Fields (son of William Jason Fields (1790) and Anna Creech (1801)) would serve in Fields' Rangers. He was married to William W. and Sallie Green's daughter Minerva since January 15, 1860.

Other family members of William W. Green had ties to Fields' unit as well. William's sister Almeda was married to John Wesley Sparks, who, with his brother Hugh Sparks, served under Fields. Two of William Wellington Green's nephews, William M. and Francis Marion Green, sons of Robert Kilgore Green, were also members.

While in Morgan County, Nancy Jane Duncan was able to briefly reunite with her daughters Lisey and Louisa who were living temporarily with William Green and his family. She found the girls, "all Well and harty and Doing Well." It was her hope to take them home with her on her next trip to Kentucky three months later. After visiting for a short while with her children and the Greens, Nancy Jane Duncan took her leave and returned to Catlettsburg, where she arrived on Saturday evening, June 28, 1862. It appears that she had a pre-arranged meeting with someone in town that may have been related to her business in Kentucky. She later mentioned that she was successful in meeting the appointment.

The following morning, after writing a letter to her friends in Cassville, Nancy Jane Duncan attended church services in Catlettsburg. Afterwards, she spent the afternoon writing a letter to William Green in Morgan County. She then took the letters to the post office and deposited them. Her plan was to leave Catlettsburg by boat that same evening in direction Cincinnati/Louisville. "A moment before she started she was surrounded at her hotel by several well known Sympathizers and was conversing rapidly ~" Matchett's spies were nearby, but "Only a few broken sentences however were overheard by my unsuspicicious eaves dropper - and, not enough to amount to prooff against her."

Matchett's trip to the post office, however, proved to be more successful. Her letters were retrieved and opened. Combined with several reports he had received about Nancy Jane Duncan's activities, Matchett felt confident that he had enough evidence to arrest her before she would be able to board a steam boat and leave town.

.jpg) |

| Nancy Jane Duncan's letter to Morgan County, Kentucky |

.jpg) |

| Nancy Jane Duncan's letter to Cassville, Virginia |

The next morning, Monday, June 30, 1862, Nancy Jane Duncan was sent off to Louisville as a prisoner. In his letter to Louisville Provost Marshal Lt. Colonel Henry Dent, Matchett stated, "Being at a loss for proper instruction I send for your apprehension Mrs Nancy Jane Duncan to gather with two letters written by her and dropped in the Post Office of this place yesterday evening and by me extracted therefrom and opened. All thes(e) things however taken in connection with several reports not necessary to detail here and those letters taken from the P.O., which she acknowledges she wrote - and which I herewith forward to you justifies me I think in apprehending her, and pursuing the course I have taken."

Her arrest was mentioned in a number of papers, including the Louisville Daily Democrat, July 10, 1862 and the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, July 12, 1862.

At this point, due to the lack of records, we lose track of Nancy Jane Duncan. The earliest prison record, Louisville Prison Register No. 1, begins in November of 1862. Names of citizens who were arrested were excluded from the register and kept separately and have not been located.

|

| Louisville Prison Register No. 1 |

At first, some female prisoners were put up in hotels, under guard. Others were taken to Barracks No. 2, a facility which normally served as a camp for paroled US soldiers. It was located on Main between Seventh and Eighth Streets. Due to the increase in numbers of female prisoners, General Boyle issued instructions on July 1, 1862, to the Provost Marshals throughout Kentucky "to fit up quarters for the imprisonment of such disloyal females" as they might find it necessary to arrest.

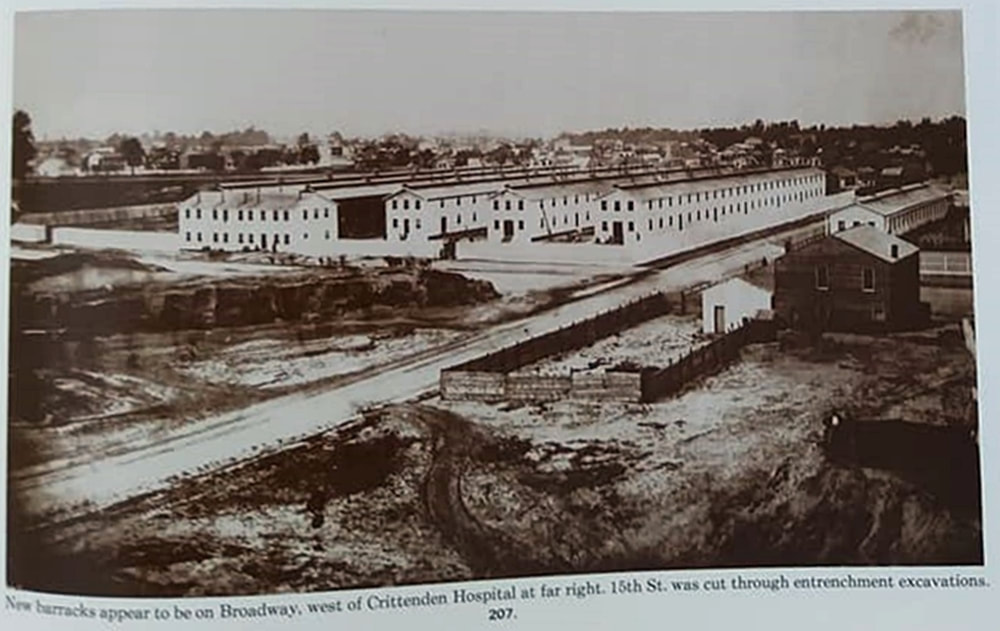

Accordingly, Union authorities in Louisville took over a large house, situated between 12th and 13th Streets, at the corner of 13th and Broadway, and converted it into a military prison for women. It was within walking distance of the regular Military Prison, the Refugee Home, the Crittenden US General Hospital and a few blocks from the L & N. Railroad Depot.

The two-story building was described as a "good dwelling-house, well ventilated and dry." The grounds surrounding the house were spacious and shaded with fruit and ornamental trees. The women were allowed the full freedom of the grounds which were enclosed by a fence. The gate was guarded by a sentry on duty at that post. The women were supplied army rations, "yet prepared in such a manner as to render them palatable even to the delicate." The rooms were modestly furnished and contained on an average three double beds. The quarters were considered "airy, comfortable, and healthy." The sick were taken care of in two of the rooms in the back part of the building. In some cases, the incarcerated women were accompanied by their children.

|

1865 map of Louisville. Red shaded area indicates the general

vicinity where the Female Military Prison was located.

Map Source: LOC |

In general, women prisoners were given several choices, depending on the severity of the charges:

- take the oath of allegiance and return home

- be jailed

- be exiled to Confederate lines, not to return for the duration of the war

- be released north of the Ohio River, not to return for the duration of the war

In absence of any type of records, it is difficult to determine which choice Nancy Jane Duncan made or what fate she and her children met. Her true identity has remained a mystery as she he may have operated under an assumed name. It is possible that further research may yet uncover a direct family connection between her and the Stone as well as the Green families. This is an on-going project and family researchers are encouraged to contact me with any additional information that may shed more light on Nancy Jane Duncan or the families she was involved with.

Researched, transcribed and written by Marlitta H. Perkins, January/July 2023. Copyright © 2023. All Rights Reserved.

Links of Interest

Source: LOC

Source: Eastern Kentucky and the Civil War

.jpg)

.jpg)

Hi there! I hope you don't mind an intrusion. I went down a research rabbit hole that led me to Lawrence County, and I found a lot of your work online. Bit off topic, but I couldn't find an email: are there any extant maps (especially plat maps) of the town of Louisa in 1861-ish? I'm researching a soldier encamped there who married a local girl and I wanted to see if I could figure out where they married. Thank you!

ReplyDelete